Militant research approach is well rooted in sociological studies. The idea of collecting data through alternative methods claws its way back to two founding fathers of social sciences, Karl Marx and Max Weber. In 1880, Karl Marx launched a 101-question survey to inquiry about the labour situation of the Revue Socialiste readers. The aim of the the questionnaire was to produce knowledge from the immanent composition of the labour force in order to foster critical knowledge from the bottom-up and, in turn, provide more tools for workers’ self-organisation. A similar purpose held Max Weber’s questionnaires, employed to study the life conditions of workers in rural areas in the East of Prussia and the effects of industrial labour in their personality and life style between 1880 and 1910. Marx and Weber, however different in their views of social philosophy and ultimate values, shared a sociological approach and agreed on a fundamental principle of the theory of knowledge of the social world.

Throughout the twentieth century, social and political movements latched onto Marx and Weber’s efforts to enable workers to carry out their own social research from the perspective of facilitating self-organisation. Since the 1950s, several theoretical currents developed a workers’ focused type of inquiry, arranging a wide variety of theoretical debates and interests. A myriad of tendencies emerged in order to provide with an emancipatory methodology. It is not the aim of this research to analyse the differential elements each of these political trends. For that purpose, I remit to the research of Marcelo Hoffman (2019), which remains the most complete and updated work offering a detailed examination of the different tendencies and a comparison between them. The interest in this contentious methodological approach is to selectively gather up the most relevant elements, concepts and theoretical strategies that this tradition has left behind, in order to develop our own research approach.

The first movement that revived workers’ questionnaire was in the United States the ‘Johnson-Forest Tendency’, a group of unorthodox American socialists that emerged out of the Trotskyist Workers’ Party in 1941. The Johnson-Forest Tendency released a short pamphlet called The American Worker (1947), which collected workers’ daily experiences at the factory through a narrative style. They collected stories of everyday working-class life, aimed at provoking class-consciousness amongst their readership. In France, an autonomous movement called ‘Socialisme ou Barbarie’ was also born in rupture to dogmatic readings of Marxism. Socialisme ou Barbarie was formed by a group of intellectuals, among which there were prominent intellectual figures such as Cornelius Castoriadis and Claude Lefort, who produced a workers’ newspaper (Tribune Ouvrière) in the Renault Billancourt factory in Paris. Like the Johnson-Forest Tendency, Socialisme ou Barbarie employed the worker’s focused inquiry through a narrative style as a powerful means of raising class-consciousness by drawing out common experiences recognizable to other workers.

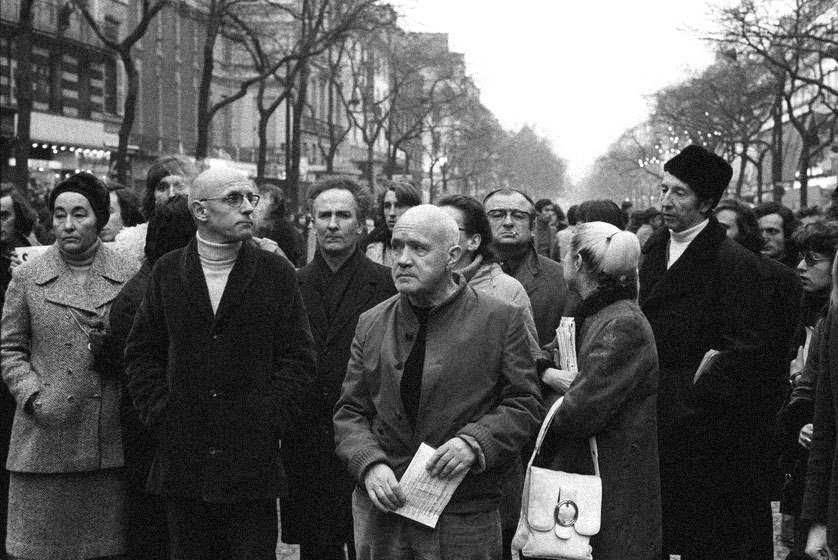

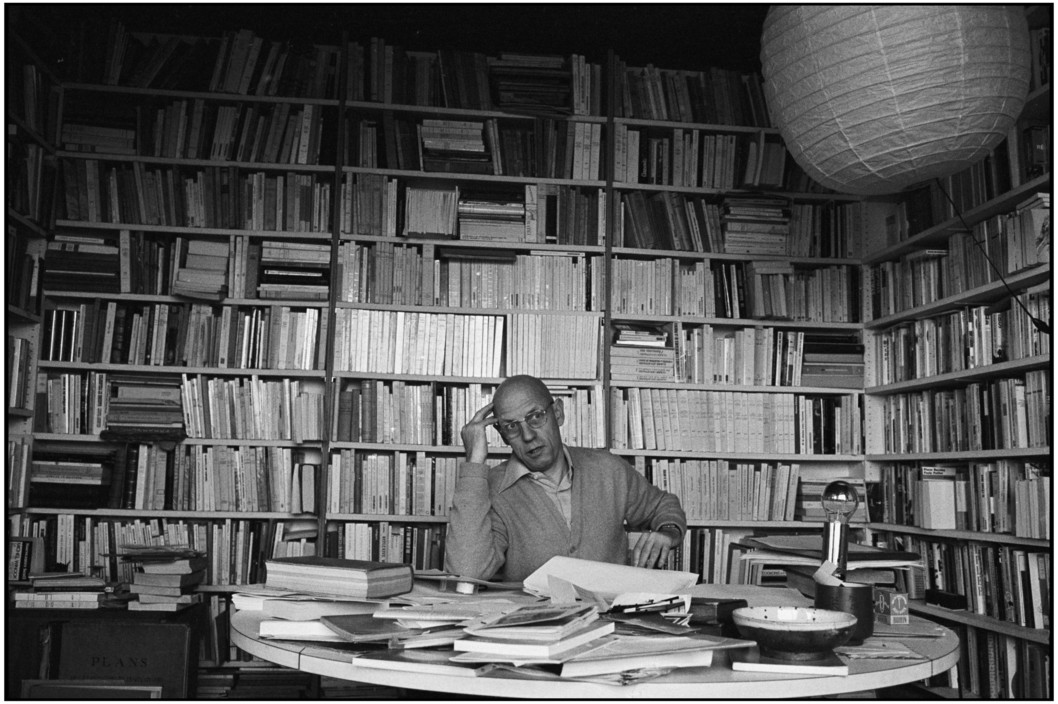

In Italy, the use of the survey as a political and sociological method of analysis was further extended within operaismo political movement. In contrast to the previous political movements, Italian operaismo placed the survey [inchiesta operaia] in the heart of the workers movement to study the new class composition. The first written outcome was the journal Quaderni Rossi, which was the political seed of operaismo, aimed to analysing the new forms of capitalist explotation and to capture the workers’ insubordination strategies. In France, there can be found the Union des Communistes de France Marxiste-Léniniste (UCFML) and the Group d’Information sur les Prisons (GIP), which deployed the enqûete in a very idiosincratic manner. Alain Badiou as the main intellectual referent in the UCFML and Michel Foucault in the GIP, both theorised and put in motion a radically different research based on a specific political commitment. At the beginning of the GIP, Foucault used the following words to make clear what was the GIP’s aim:

« Le Groupe d’information sur les prisons vient de lancer sa première enquête. Ce n’est pas une enquête de sociologues. Il s’agit de laisser la parole à ceux qui ont une expérience de la prison. Non pas qu’ils aient besoin qu’on les aide à « prendre conscience »: la conscience de l’oppression est là, parfaitement claire, sachant bien qui est l’ennemi. Mais le système actuel lui refuse les moyens de se formuler, de s’organiser.

(…)

Notre enquête n’est pas faite pour accumuler des connaissances, mais pour accroître notre intolérance et en faire une intolérance active.

(…)

Comme premier acte de cette « enquête-intolérance », un questionnaire est distribué régulièrement aux portes de certaines prisons et à tous ceux qui peuvent savoir ou qui veulent agir. »

M. Foucault, “Sur les prisons”, J’accuse, nº3, 15th March 1971, reproduced in M. Foucault, Dits et Écrits, vol. II, text nº87, pp.175-6

In terms of methodology, the different currents of militant research deployed a varied range of sociological tools: surveys, in-depth interviews, fact-finding meetings, individual narratives and other forms of writing. What all these types of militant research have in common, however, is that their research aimed at producing a collective, antagonist subjectivity rather than extracting data in order to publish academic content through mere informational contents. Despite the fact that their research methods differed, they shared the view of doing research as a means of raising the political consciousness of the subjects involved in their research.